Here, we show the functionality of an SDForest and how you can use it to screen for causal parents of a continuous response in a large set of observed covariates, even in the presence of hidden confounding. We also provide methods to asses the functional partial dependence of the response on the causal parents.

We show the functionalities with simulated data from a confounded

model with one true causal parents of

,

see simulate_data_nonlinear().

library(SDModels)

set.seed(42)

# simulation of confounded data

q <- 2 # dimension of confounding

p <- 350 # number of overved covariates

n <- 400 # number of obervations

m <- 1 # number of causal parents in covariates

sim_data <- simulate_data_nonlinear(q = q, p = p, n = n, m = m)

X <- sim_data$X

Y <- sim_data$Y

train_data <- data.frame(X, Y)

# causal parents of y

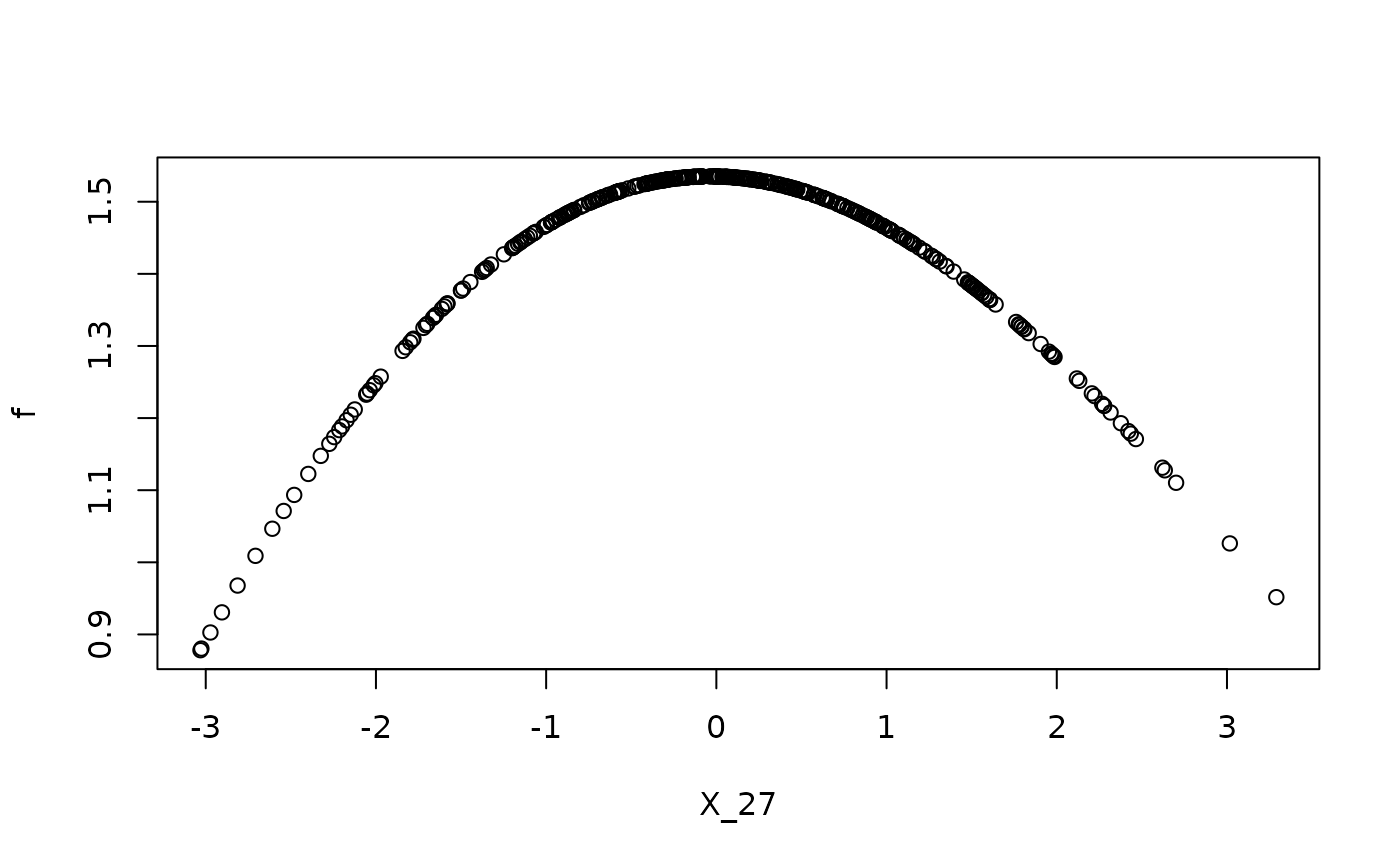

f <- apply(X, 1, function(x) f_four(x, sim_data$beta, sim_data$j))

# functional dependence on causal parents

plot(x = X[, sim_data$j], f, xlab = paste0('X_', sim_data$j))

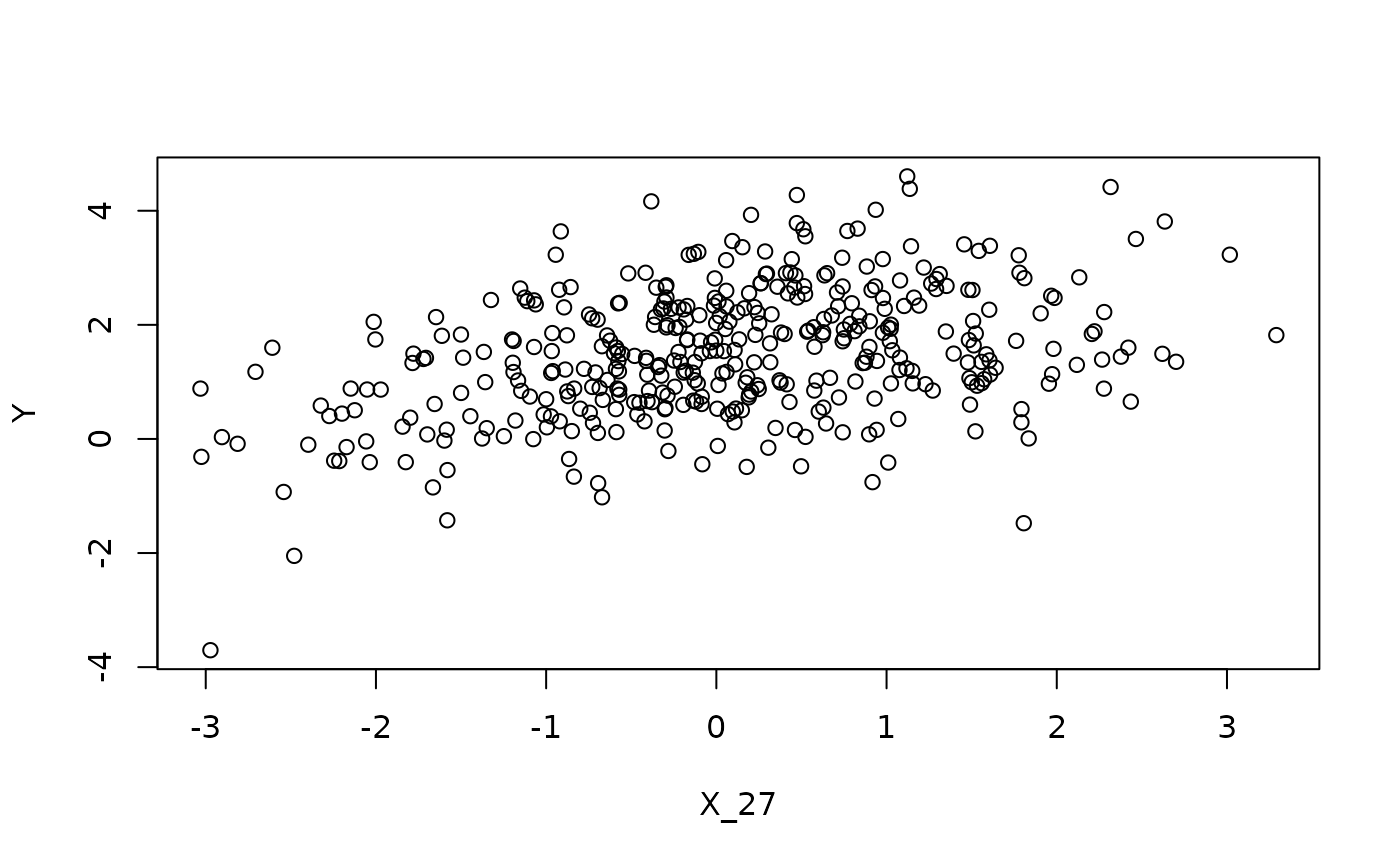

# observed dependence on causal parents

plot(x = X[, sim_data$j], Y, xlab = paste0('X_', sim_data$j))

We first estimate the random forest using the spectral objective:

where is a spectral transformation. (Ćevid, Bühlmann, and Meinshausen 2020)

fit <- SDForest(Y ~ ., train_data)

fit

#> SDForest result

#>

#> Number of trees: 100

#> Number of covariates: 350

#> OOB loss: 1.19

#> OOB spectral loss: 0.02Causal parents

Given the estimated causal function, the first question we might want

to answer is which of the covariates are the causal parents of the

response. If we intervene on the causal parents, we expect the response

to change. For that, we can estimate the functional dependency of

on

,

and examine which covariates are important in this function. We can

directly compare the importance pattern of the deconfounded estimator to

the classical random forest estimated by ranger. This comparison to

the plain counterpart always gives a feeling of the strength of

confounding. If no confounding exists, SDForest() and

ranger::ranger() should result in similar models.

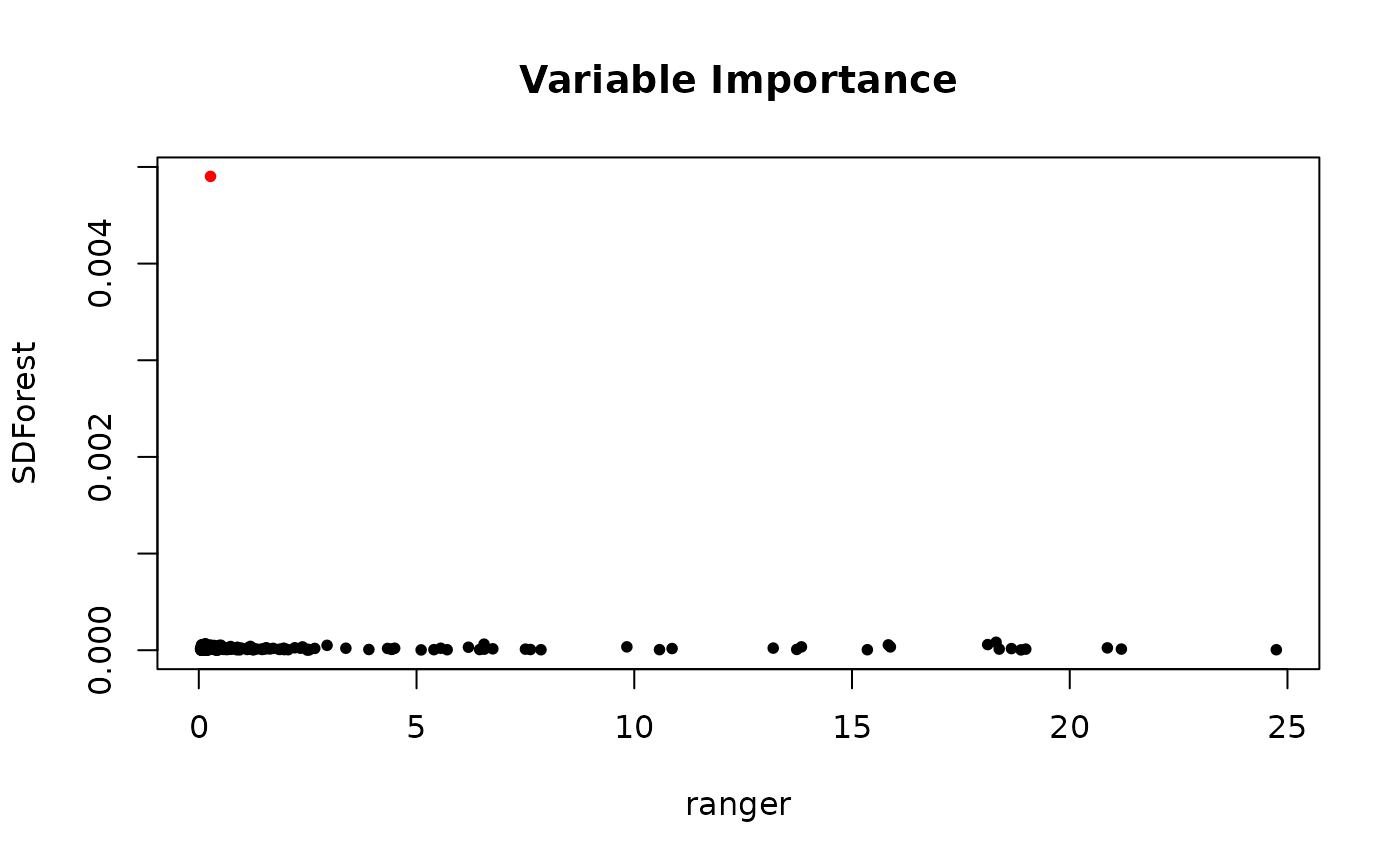

In the graph below, we see the variable importance

varImp() of the deconfounded random forest against the

plain random forest. The scale has no meaning, but we see how the true

causal parents in red is getting a clear higher variable importance for

the SDForest. The plain random forest cannot distinguish between

spurious correlation and true causation.

# comparison to classical random forest

fit_ranger <- ranger::ranger(Y ~ ., train_data, importance = 'impurity')

# comparison of variable importance

imp_ranger <- fit_ranger$variable.importance

imp_sdf <- fit$var_importance

imp_col <- rep('black', length(imp_ranger))

imp_col[sim_data$j] <- 'red'

plot(imp_ranger, imp_sdf, col = imp_col, pch = 20,

xlab = 'ranger', ylab = 'SDForest',

main = 'Variable Importance')

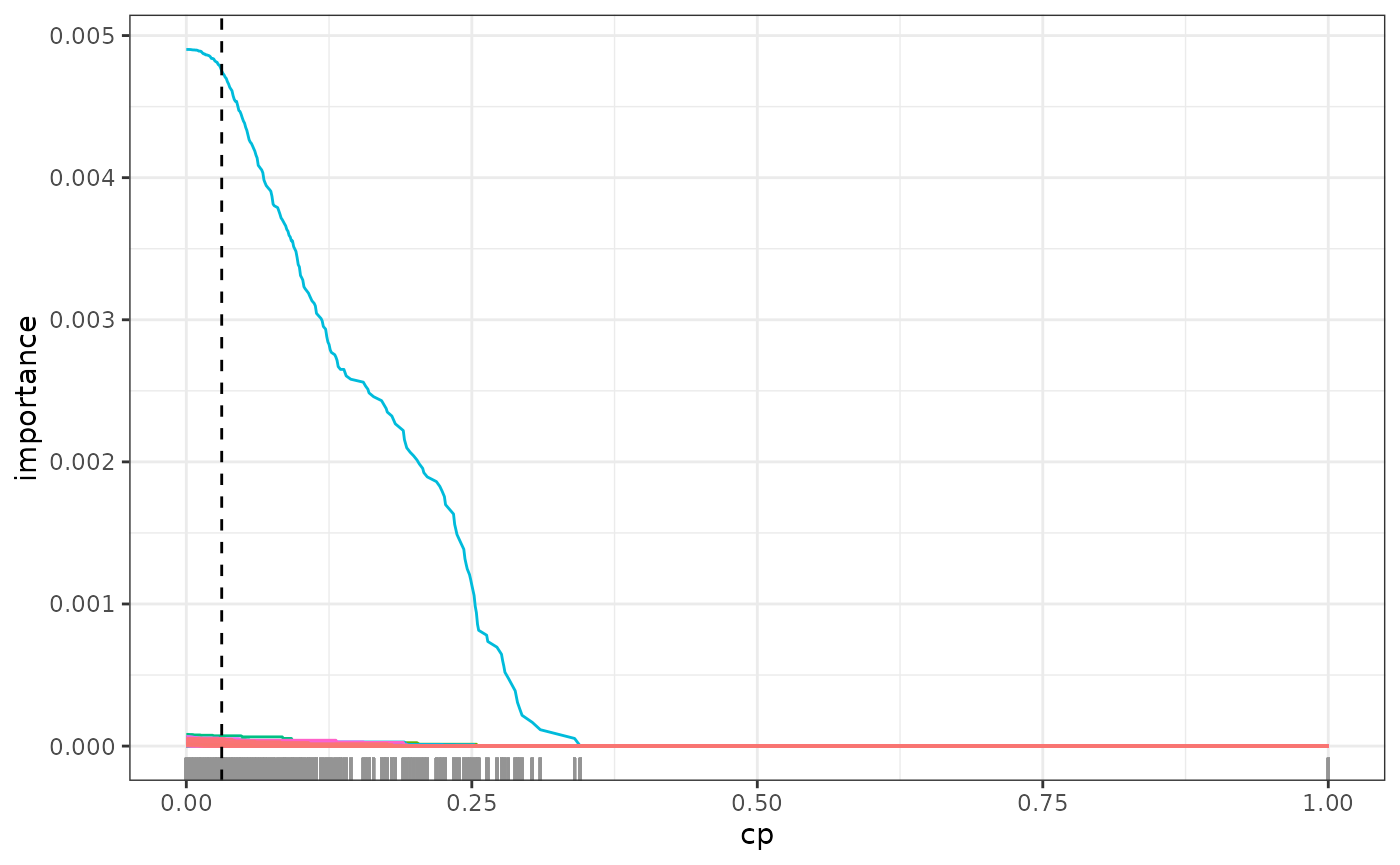

Before, we looked at the variable importance of the non-regularized

SDForest. We have two more techniques to better understand which

variables might be causally important. The first is the regularization

path regPath(), where we plot the variable importance

against varying regularization, i.e. different cp values.

The option plotly = TRUE lets us visualize these paths

interactively to better understand which covariates seem to have robust

importance in the model.

# select 20 most important covariates for further exploration

most_imp <- fit$var_importance > sort(fit$var_importance, decreasing = TRUE)[20]

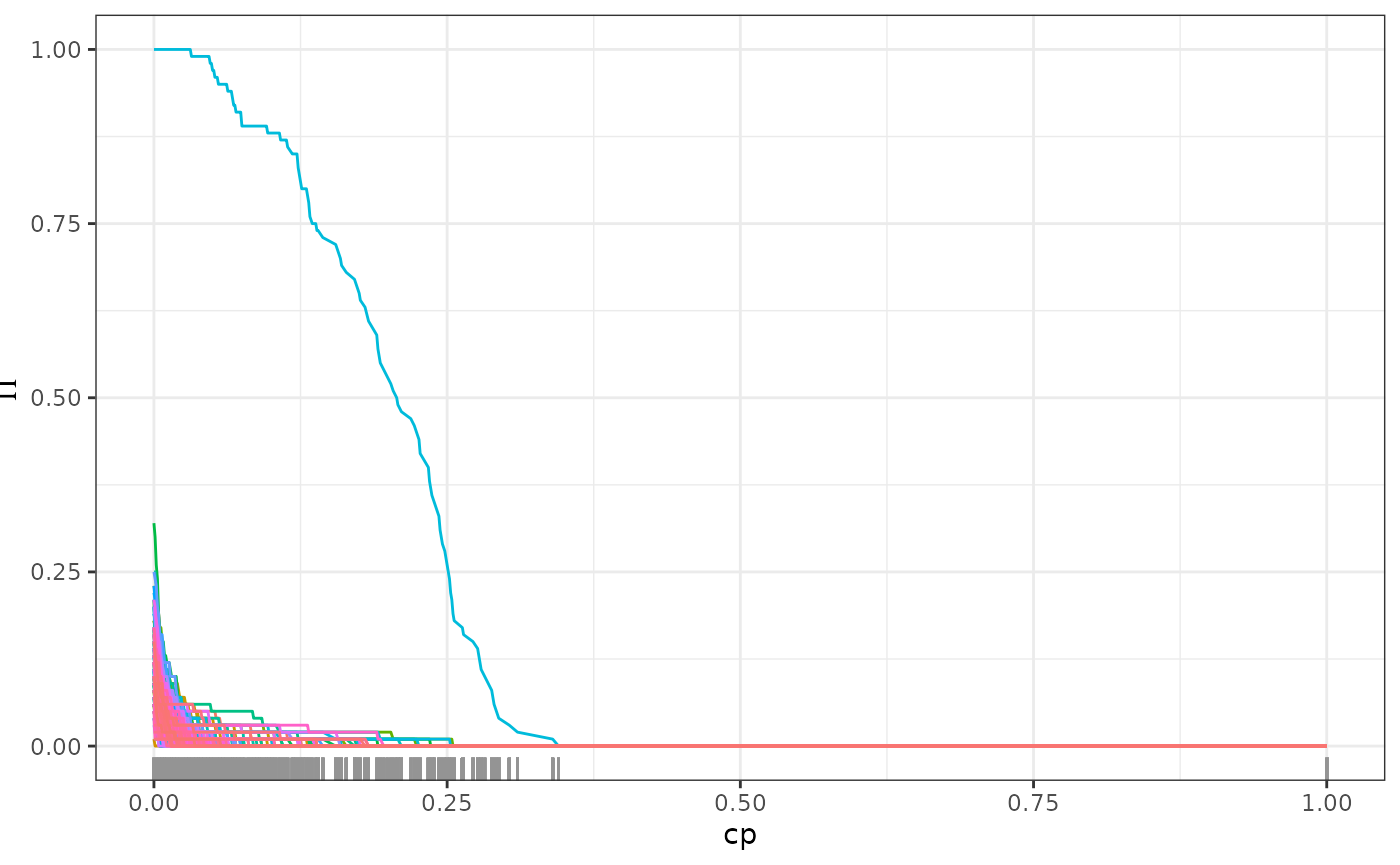

plot(path, plotly = TRUE, most_imp)The second method follows the stability selection approach (Meinshausen and Bühlmann 2010). Here, we visualize the proportion of trees in the forest that use each covariate for splits in the model. As we regularize more, only the truly causal important variables will still be used by most trees.

# detection of causal parent using stability selection

stablePath <- stabilitySelection(fit)

#plot(stablePath, plotly = TRUE)

plot(stablePath)

Causal dependence

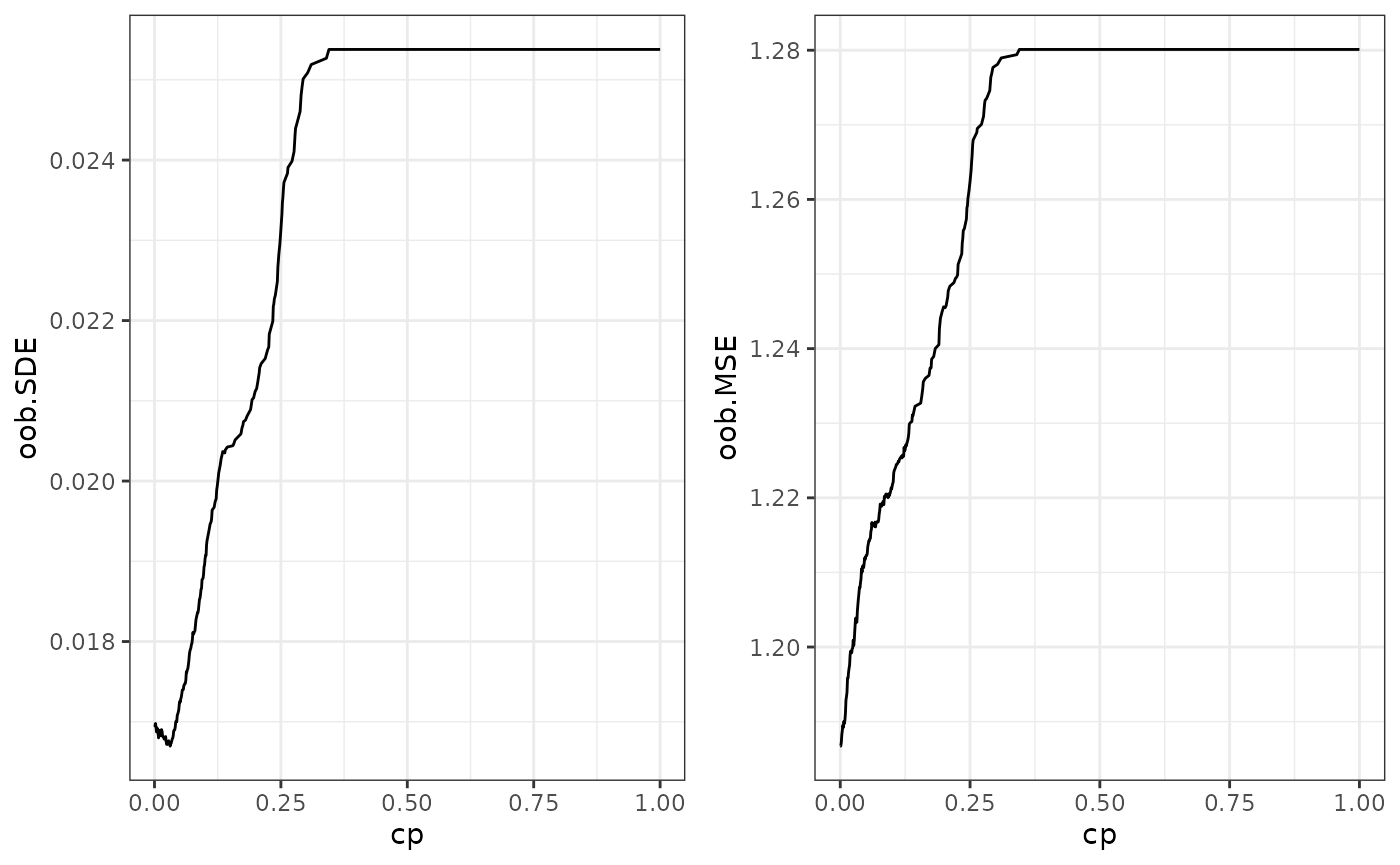

After finding the causal parent of the response, one might be

interested in the partial functional dependence of

on the causal parents. If we want to intervene in a system, we need to

not only know where to intervene but also how to intervene in order to

get the desired response. For that, we first prune the forest to remove

any residual spurious correlation and get optimal predictive power. For

that, regPath() also contains the out-of-bag prediction

errors for different regularizations. plotOOB() visualizes

both the mean squared error (oob.MSE) and the spectral loss (oob.SDE)

that we minimize. The minimal out-of-bag error lets us choose the

optimal cp value to prune the forest.

# out of bag error for different regularization

plotOOB(path)

path$cp_min

#> [1] 0.031

# pruning of forest according to optimal out-of-bag performance

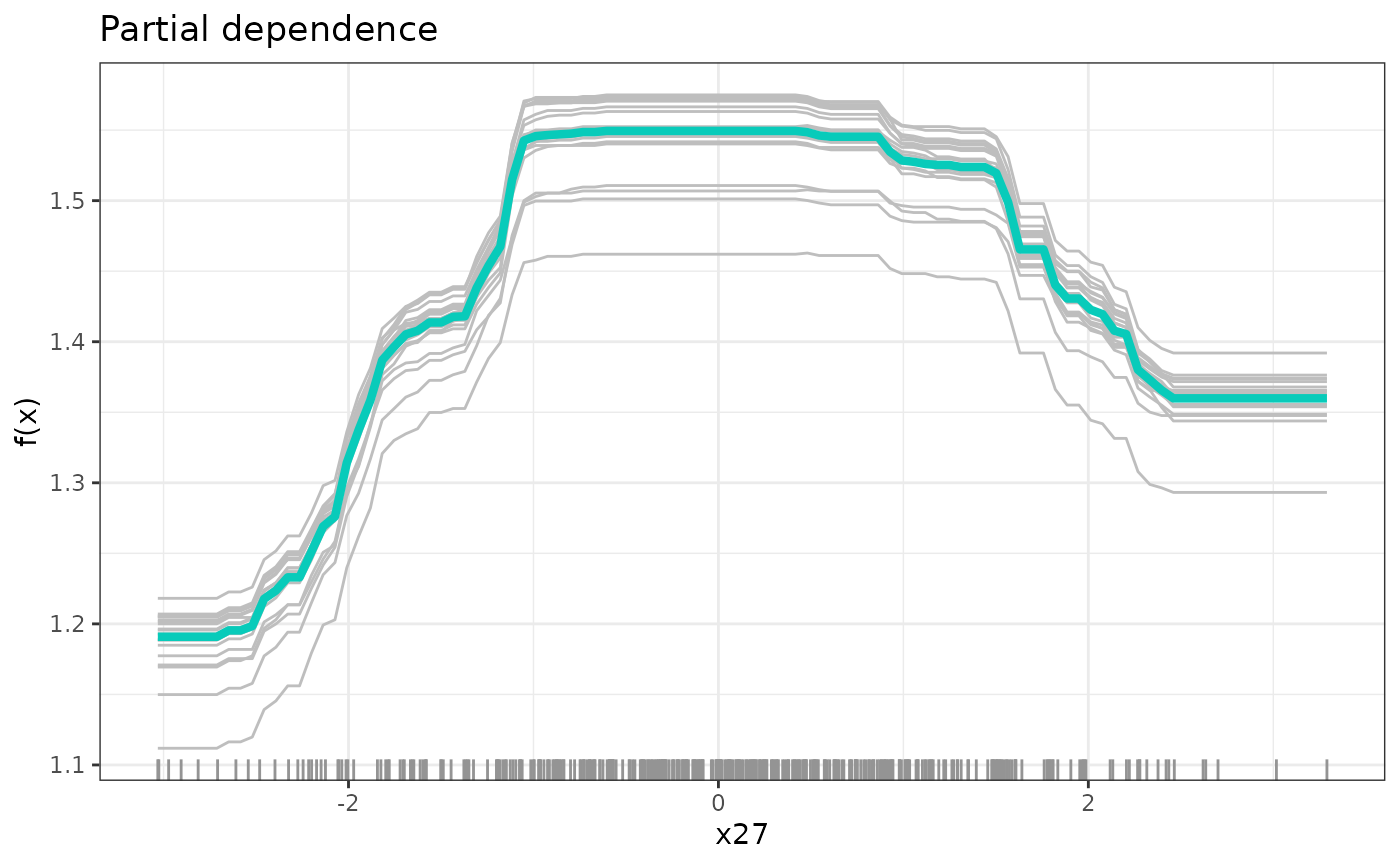

fit <- prune(fit, cp = path$cp_min)Now, to distil the partial functional dependence of the response on

the causal parents, we use partial dependence plots in

partDependence() (Friedman

2001). For that, we vary the value of one covariate while fixing

the others to the ones that we actually observe in the data. As

representative partial conditional dependence, we plot the mean over

these individual response curves in addition to a few sample

individuals.

# partial functional dependence of y on the first causal parent

dep <- partDependence(fit, sim_data$j)

plot(dep)